September 15, 2025

LLMs can help persuade parents to vaccinate their kids.

If vaccination rates continue to fall, dreadful diseases will roar back

As vaccination rates continue to drop, epidemiologists have been sounding increasingly loud warnings. Kiang et al. modelled re‑emergence under declining vaccination scenarios and found that at today’s state‑level coverage, measles may become endemic again. Their model shows that a further 50% drop in childhood vaccination over 25 years would yield ~51 million measles cases (plus 10 million rubella cases and more than 4.3 million polio cases), more than 10 million hospitalizations, and ~160,000 deaths. Because these diseases are so contagious, the effect of declining vaccination rates is highly non-linear. Even a 10% drop plausibly translates into millions of additional cases and thousands of preventable deaths over a generation.

I’m trying to do something about this looming disaster

I’m exploring ways to help stem the rising tide of vaccination refusal and spare a generation of children from deadly preventable diseases like measles. Specifically, I hypothesize that LLMs can help with this problem. I suspect that their encyclopedic knowledge, infinite patience, and ability to be resolutely non-judgmental can be a powerful force for good here.

Earlier this year I ran a first experiment, and found that both a brief LLM chat and a mandatory review of some carefully written static materials boosted parental vaccine intent modestly. I saw suggestive evidence that both were effective, although neither mode was clearly superior to the other.

Now I’ve completed a second trial applying some lessons learned from the first one.

The focus: MMR-hesitant U.S.-based parents of kids under the age of 6

I recruited U.S.-resident parents of young children who at some point expressed to Prolific that they had less than complete confidence in the safety of childhood vaccines. But as I discovered in my first experiment, many such parents are actually not hesitant in practice.

So to focus on parents who have real qualms, this RCT included a two-phase screening process.

First parents were asked to imagine receiving a message from their pediatric medical provider a week before an appointment indicating that their child is due to receive a dose of the MMR vaccine, with two buttons: I have questions or concerns about MMR, and No questions or concerns about MMR. Only parents with questions or concerns proceeded. More than half of the participants exited at this point (284 of 497, ~57%).

Those remaining were asked:

At your well-visit next week, do you intend to have your child receive the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine?

Only parents whose baseline intention was 6 or less on a 1-7 scale (1 = “Definitely not”, 7=“Definitely yes”) were randomized into the treatment or control group. An additional 33 participants (15% of the remaining 213) exited at this point, with 180 proceeding.

Overall even with a starting pool of parents somewhat enriched for vaccine skepticism, only about one in three (180 of 497, 36%) of those who saw the mock‑appointment step proceeded to randomization (N = 180). At least with this specific setup and sample, vaccine skepticism didn’t always translate directly into practical reluctance.

Those who remained were mostly young, conservative-leaning women. The randomized sample skewed female (≈69%) and conservative (≈52%), with a majority in the 25–34 age bracket (≈51%) and most of the remainder 35–44 (≈34%).

I applied some lessons from the first experiment

In RCT1, both of the interventions I tried seemed to work, leading me to wonder…why not both? So this time I combined them. Parents in the treatment group were asked to review some factual material about the MMR vaccine, and then to engage in a brief chat with an LLM (Claude 4 Sonnet).1 Parents in the control completed a parallel experience, matched in structure, but covering a topic unrelated to vaccines (car seat safety).

The control group in this experiment is thus a much closer match to the pre-appointment experience for most parents, namely no particular preparation for the vaccine discussion and decision at all!

I made a few other changes as well:

- The static content was more engaging and vivid, including visualizations of the relative risks of the vaccine vs. the measles virus itself, as well as an element of anticipated regret, telling stories of parents who regretted their decisions not to vaccinate their children, and inviting the participants to imagine that scenario. The content in RCT1 hewed more closely to the dry, factual tone of standard CDC materials.

- The prompts were constructed to use motivational‑interviewing-style techniques to mitigate the risk of reactance, and to persistently emphasize parental autonomy.

- Participants were asked to imagine an upcoming appointment, instructed that the purpose of their chat was to prepare for that visit, and that a summary of their chat transcript would be provided to their clinician.

Treatment group parents increased their MMR intent by a full point on the 7 point scale

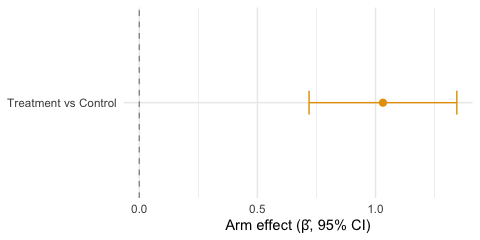

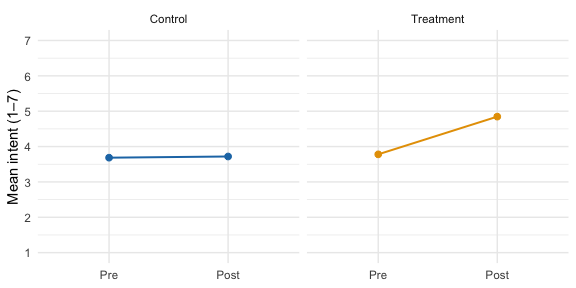

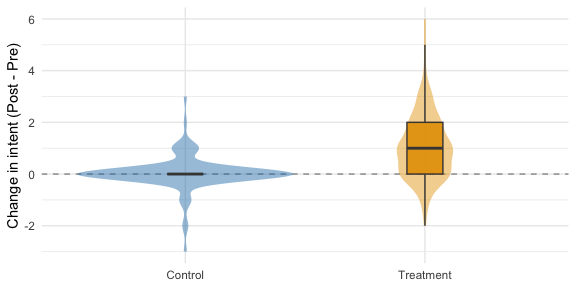

Control group parents’ vaccination intent did not meaningfully change (+≈0.03). On average, treatment group parents, by contrast, increased their vaccination intent by more than a full point (+≈1.07). The adjusted Treatment–Control difference was β̂ ≈ 1.03; 95% CI 0.72–1.34. Nearly two thirds (~64%) of treatment group parents increased their intention by at least one point vs only about 1 in 10 in the control group.

Adjusted Treatment–Control effect (95% CI)

Pre vs Post mean intention by arm

Treatment vs. Control vaccination intent change (violin and box plot)

The transcripts show persuasion in action and surface useful context for clinicians

As in the previous experiment, the LLM conversations were illuminating and occasionally exasperating.

In several cases, correcting a single concrete misconception (e.g. “the MMR vaccine does not contain aluminum, or mRNA”) appears to have been sufficient to overcome hesitations:

I am more likely to allow my child to receive vaccination lnowing it doesnt contain aluminum

In other cases anxiety seemed to soften when parents were given an actionable plan for what to expect. A parent who asked…

Is there anyway to prepare ahead for these likely side effects?

…received some detailed practical suggestions, and then responded:

“I think a preparation plan makes me more eased up”

A subset of parents expressed well-grounded hesitations, like a history of seizures or anaphylaxis. These encounters tended not to yield changes in intent, but they surfaced context that might help a pediatrician better prepare for a complicated conversation.

The effect appears to be durable over a period of at least several days

A software bug caused the post-intervention survey not to be presented to the first cohort of 90 participants I recruited for this study. Unfortunate! But also unintentionally illuminating: I re-contacted these parents for a short follow-up survey on Prolific and collected a post-intervention 1-7 intention score from 66 of them.

The median delay was ~2 days (range ≈ 0.3–7.1 days). Using that delayed post-intent as the outcome, the adjusted Treatment–Control difference was about the same as the immediate effect: β̂ ≈ 1.09 (95% CI 0.52–1.66; N = 66). Slicing the sample into three equal-sized delay windows, the effect is consistent across all three: ~+1.01 for the shortest window (≤1.6 days), +0.94 for 1.6–2.1 days, and +1.59 for >2.1 days.

This is a smaller, opportunistic sample, so take it with a grain of salt as exploratory, but it points the same direction as the primary result, and suggests that the effect persists over at least several days.

Next step: a clinical pilot

This study, like the first one, has self-reported vaccination intent as its endpoint. It’s a good first step, but obviously it’s not the same as shots in arms.

My working plan is to wire something very much like what we tested here into a pediatric clinical workflow: a pre‑visit message routing hesitant parents into the intervention, then feeding a brief summary and context to the pediatric provider. The endpoint would be EHR‑confirmed on‑time MMR within 30 days.

By the way, these diseases are horrific

Imagine your child gets measles as an infant, before they’re old enough to be vaccinated, in one of our increasingly frequent outbreaks. They’re lucky; they don’t get encephalitis (~1 in 1,000) or pneumonia (~1 in 20), they’re not hospitalized (~1 in 4 in the U.S.), they don’t die (1–3 in 1,000) (CDC clinical overview. But years later they start forgetting words, nodding off at dinner, then seizing and no longer recognizing your face. They have subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a delayed complication of measles that’s almost always fatal. I included a mother’s account of SSPE in the materials I asked participants in this experiment to read, and LA County just reported the death of another child who caught measles in infancy and developed SSPE. It’s rare (~1 in 10,000) but the risk is far higher (about 1 in 600) when the infection happens in infancy (LA County public health).

Parents see endless myths about vaccine harms but few know about the very real and devastating risks of the virus itself. I think we have tools at our disposal now that can respect their autonomy while patiently and respectfully helping them to understand and weigh the risks, and then act accordingly.

Interested in collaborating?

If you run a pediatric practice and are interested in collaborating on a lightweight pilot, or if you’d like to support this work in any way, please reach out.

Full analysis and preregistration

Specifically Claude 4.0 Sonnet via the Anthropic API (

claude-sonnet-4-20250514), with thinking enabled. ↩︎